In the pre-antitrust U.S. banking industry, then, networks known as clearinghouses arose to reduce transactions costs and bolster reputations. “An essential feature of the banking industry was the endogenous development of the clearinghouse, a governing association of banks to which individual banks voluntarily abrogated certain rights and powers normally held by firms.” Membership requirements and monitoring enhanced the public’s trust in the redeemability of members’ bank notes and the overall soundness of their business practices. As Gorton and Mullineaux (1987) explain:

The clearinghouse required, for example, that member institutions satisfy an admissions test (based on certification of adequate capital), pay an admissions fee, and submit to periodic exams (audits) by the clearinghouse. Members who failed to satisfy [commercial-bank clearinghouse] regulations were subject to disciplinary actions (fines) and, for extreme violations, could be expelled. Expulsion from the clearinghouse was a clear negative signal concerning the quality of the bank’s liabilities. . . .

An additional check against collusion was banks’ credible threat to withdraw from the network or refuse to join. As Dowd recounts:

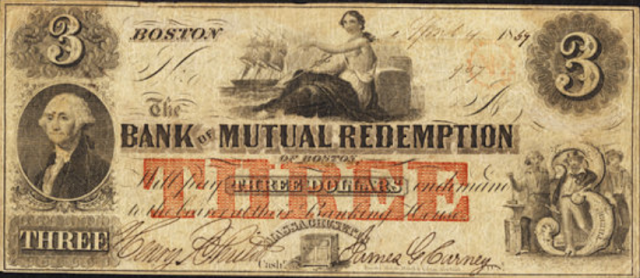

A good example of banks “voting with their feet” even when the market could only support one clearinghouse is provided by the demise of the Suffolk system. The Suffolk system was a club managed by the Suffolk Bank of Boston, but some members found the club rules too constraining and there were complaints about the Suffolk’s highhanded attitude toward members. Discontent led to the founding of a rival, the Bank of Mutual Redemption (BMR), and when the latter opened in 1858 many of the Suffolk’s clients defected to it.

—Bryan Caplan and Edward P. Stringham, “Networks, Law, and the Paradox of Cooperation,” in

Anarchy and the Law: The Political Economy of Choice, ed. Edward P. Stringham (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007), 305-306.

No comments:

Post a Comment